You are here

Morning Meeting in Port-au-Prince

Today, like all days here, begins with a meeting. Amid the hectic aftermath of the Haitian earthquake, these 30 minutes or so are the only time all eight of CDC’s surveillance and response team are likely to be together in the same room until the last hours of the day. And it is certainly the last any of them will sit still today.

It is difficult to detail the pace of an emergency. Each brings its own energy, unfurled to a soundtrack of cell phone rings and the heavy drone of low flying cargo planes. Here at the National Laboratory of Public Health in Port-au-Prince, home base for the surveillance and response team, CDC staff members bring a wide range of expertise to the crisis, and each morning that expertise flows over a round plastic table in a corner of the lab’s former cafeteria, its pale yellow walls cracked from the force of the quake.

It is here that microbiologists, EIS officers and vaccine specialists plot another long day of response to the Haitian disaster. The conversation moves quickly – short answers to short questions, the day divided into manageable tasks and finite goals realized and lost on the myriad foibles of a disaster response. It is often a soup of questions: What is the state of tuberculosis care? Do health agencies know who to report cases to, and if so, can patients access medicine? Who speaks English and when she leaves, will her replacement be bilingual? How many stool kits have we got? What’s the word on the malaria rapid test kits? Who is coming to the camp tomorrow, and how many cars will we need? Who is on dengue cases and what have you got?

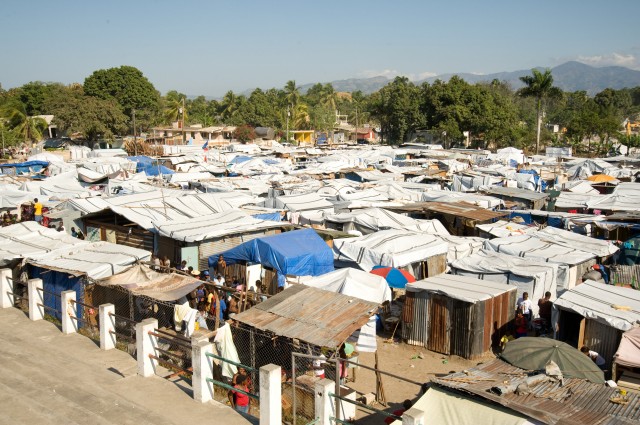

In Haiti today information from last night is old. Information from yesterday morning is ancient and people you worked with last week are home in Norway, Puerto Rico or Boston today. Their replacements are meeting your replacements, as agencies cycle new staff in to Haiti to give exhausted relief workers a break. For the CDC team, the goal is coordination and surveillance, as camps crowded with Haiti’s displaced offer rich breeding grounds for any of a score of infectious diseases, from malaria and dysentery to typhoid and dengue. Camp visits help staff to see firsthand what’s really going on – information is everything. They need to know how many are in any given camp, what care they are receiving from aid agencies, and if those agencies know how and to whom to report any cases of infectious disease. Outbreak is on everyone’s mind.

Here on the grounds of the lab, the staff members sleep in tents – men outside on the roof, women in the same small cafeteria that serves as both office and dining room. There are no formal hours. People work until they can’t, generally, and eat what they can, when they can. A plastic fan blows humid air across the room – low 90s during the day, mid-70s at night. Between the laptops and plastic pencil cups, the single table is stacked with a dozen plastic bags and labeled packets of any day’s meals – a scene part office supply store, part camping trip, part bachelor pad. The main meals are snacks. There is no time for long meals, and the dull plastic packets of military meals ready to eat – MREs – sit stacked in a corner box. No one likes them, but they eat them because they’re here, each cleverly named in the laconic vernacular of the military that produced them, and each densely packed with enough fat and calories to keep hungry soldiers going in extreme conditions. The Strawberry Banana Dairyshake, for example – a plastic packet the main ingredient of which is powdered milk – has 460 calories, 19 grams of fat and 56 grams of carbohydrates. It turns pink when you add water and tastes nothing like you want it to.

Days are long and things catch up to you. Two of the four Puerto Rican nurses at the makeshift field hospital on the front lawn of the lab have themselves fallen ill. They were out last night, IVs in their arms, trying to catch a bit of evening breeze outside the sweltering tents, used initially as surgical tents by Belgian Special Forces in the days after the quake. When the flaps are open you catch glimpses of what the people here have suffered – a young girl on a green stretcher, her left leg missing nearly at the hip, or an elderly woman making her way awkwardly across the lawn with new crutches.

For every meeting like the one around the table this morning, there are a thousand others going on across Haiti today. For every aid worker who leaves exhausted, there is another coming. And every day, at least once, you remind yourself to be thankful for every thing and every one you have in your life.